December - January 2023

Lighting the Darkness

------------------

|

Why Should a 21st Century Christian Care About the Church Fathers?

By Kevin Hester

We must avoid two opposite errors when thinking about the church fathers. First, we must avoid what C. S. Lewis described as “chronological snobbery,” the “uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate of our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that count discredited.” In other words, if it is old, it can’t be true or right or good. But current fashion is never a sure guide. Just ask bell bottoms and penny loafers!

The second error is the enshrinement of the church fathers as infallible guides when it comes to theology, Scripture, and the faith. Unlike other traditions, Protestants have always recognized that, as fallible humans, the fathers could, and often did, make mistakes.

Instead, evangelicals should adopt a balanced approach regarding the church fathers like that of Protestant Reformers, what Timothy George describes as “retrieval for the sake of renewal.” Our goal in learning from the church fathers is not to copy them or their methods exactly. We know their practices and applications were culturally bound, just like ours. At the same time, the fathers provide us with a treasure trove of wisdom from which we can draw.

The Protestant Reformers believed reading the fathers would lead them to a better understanding of Christian theology and church practice. They wanted to purify doctrine and understand Scripture. They recognized God’s sovereignty in history and saw the early church as revelatory insofar as they followed Scripture.

With these things in mind, I offer below a brief apologetic for why today’s Christian should care about the church fathers (and Christian history in general), why you should read their writings, and how they can help you today.

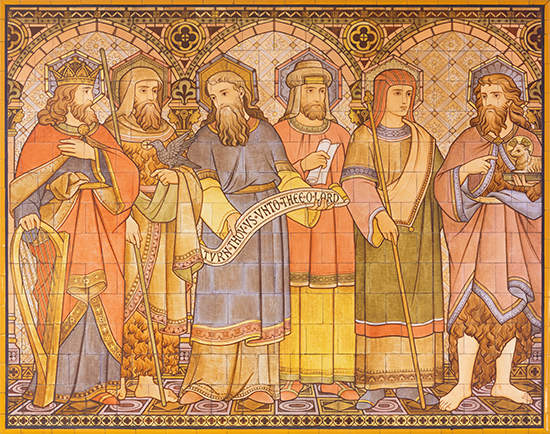

They were Christians and pastors like us. Most people imagine the church fathers as a collection of elderly men sitting around in robes debating which Greek term should be used to describe the Trinity. Or perhaps they picture half-naked ascetics wandering the desert gaunt and alone.

While the fathers often wrote on theological topics, and an ascetic community did arise after the fourth century, most church fathers were involved in pastoral ministry as bishops, elders, pastors, and deacons. They cared deeply about what they called the “care of souls.” Their writings and sermons bear witness to this. They were committed to spiritual growth, thinking deeply about what it meant to live as a Christian in a broken world. They practiced the spiritual disciplines and wrote on their usefulness for the spiritual life. In the church fathers, we find our brothers.

They lived and ministered in a world like our own. The ancient Roman world is the only historical age that readily equates to the multicultural diversity and information overload in our own day. The Pax Romana (Peace of Rome) introduced a period during which the entirety of the known world was under a single government and largely spoke one language.

The Roman world was a melting pot of cultures, religions, and vices. Ideas and religious concepts circulated freely. The multiculturalism of this period brought philosophies from Egypt, the Middle East, Greece, and Rome together. Various temple cults promoted idolatry and sexual immorality in a debauched age. It was a period of rampant and confused sexual behavior (read Romans 1 or Tertullian’s De Spectaculis).

The early Christians taught and wrote against all types of immorality including abortion and infanticide. Theologians argued against faulty scientific views like atomism, which taught matter was all that existed. They fought philosophical views that argued against the existence of truth (skepticism), and against astrological cults that played themselves off as scientific (Gnostics, Manichaeanism).

They had the same missional purpose. Earlier, I described this article as an “apologetic” for the church fathers. If you are unfamiliar with this term, it simply means a “reasoned defense.” Many in Christian circles today use the word to describe a Christian writing or argument for Christian truth against certain scientific or philosophical objections.

People often describe the writings of C. S. Lewis or Francis Schaeffer as apologetics. We often think of this as a modern invention. However, the church fathers invented apologetics to explain Christianity to the educated elite of their day. They took philosophical categories and adopted the rhetorical style of their age to present the gospel clearly and to argue for Christianity’s claims for truth.

They faced similar theological questions. The process of developing apologetics led to the adoption of philosophical structures and language that became the basis of what we call theology today. As debates emerged in Christianity about the best way to understand certain passages of Scripture, or how to express certain teachings, these discussions borrowed from the methods of the apologists. The first theological works are, in many respects, apologies for a particular interpretation of Scripture or a particular understanding of Christian teaching.

In their writings, we see theology develop. Their wrestling with different languages and ideas in real time helps us understand the language and concepts ultimately adopted and codified into the creeds and councils of the ancient church. We often answer reflexively that the Trinity is one God in three persons. What we don’t realize is that this understanding took 300 years to develop. While the Church has always embraced the full divinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and has always taught that God is one, finding the best language to communicate these truths accurately was a trial-and-error process. The early fathers were led by the Spirit in conversation with Scripture and culture.

The more we know about this process, the better we can understand theology in general and how to express difficult theological statements in a way that accords with Scripture while remaining relevant to culture.

They were closer to the events and the culture in which the New Testament was written. The church fathers were committed to the kerygma (proclamation of the gospel) of the apostles and sought to remain consistent with their teachings at all costs. In ecclesial practice, theology, and exegesis, they expounded the tradition handed down to them. Over and over, they refer to the “deposit of faith” they believed guided them in the interpretation of Scripture. This deposit of faith informed the early creeds and councils of the church.

The fathers were close (chronologically) to the writings of the apostles both historically and culturally. This aided their understanding of the text. Living only a few centuries after Christ, their environment allowed for depth in context and understanding of the text that can surpass even modern exegetes. We should take care to hear their voice and consider their reading of Scripture.

We find help in their commentaries and their sermons, and from these “old wine skins” we can draw out teachings that, although not new in themselves, seem new to us. As we reflect upon them, their depth will inspire us to the same commitment: faithfully hearing, teaching, and preaching the Word of God to our culture.

Like the faithful generations of the Old Testament, the early church fathers are an important part of the “cloud of witnesses” described in Hebrews 12. We need them. Our generation needs to know we aren’t alone in our struggles against a sinful, idolatrous culture. We must remember we are part of a rich, continuous history of Christians who looked to Scripture for answers. We aren’t the first to encounter the biblical texts we strive to apply to our lives and explain to our congregations and classes.

Christians today need the wisdom of those who have gone before. Let us follow their examples and avoid their mistakes. Let us look to them as brothers and sisters in Christ who desired for us to grow in faith and Christlikeness. They are waiting to sharpen us as iron sharpens iron. Therefore, in the words of St. Augustine:

Tolle, lege. Take, and read!

About the Author: Dr. Kevin Hester is vice president for institutional effectiveness at Welch College, where he additionally serves as senior professor of divinity, dean of the School of Theology, and program coordinator for theological studies.

|

|