August-

September 2011

Extraordinary

Families

E-Reader

About ONE

----------------------

|

This year marks the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible.

The King of Books

by Danny Conn

This year marks a unique milestone in Bible history: 2011 is the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible. No other book has exerted such an influence on the world. A review of the history and climate of its production will help us appreciate the profound impact this translation has had on the English-speaking world.

In 1567, James VI, king of Scotland came to the throne after his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate the crown. Mary was a staunch Roman Catholic, but the Scottish lords were Protestants. When Queen Elizabeth of England died in 1603, her cousin James VI of Scotland became James I of England.

As the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, James took an active role in matters of the church. Shortly after assuming the throne, he called for a meeting to hear of the “things pretended to be amiss in the Church,” which stemmed from complaints made by the Puritans. The Hampton Court Conference, January 1604, was convened to hear these matters. Puritan leader, Dr. John Reynolds, proposed a new translation of the Bible, and although the suggestion met some resistance, it caught the attention of the king.

The Work Commissioned

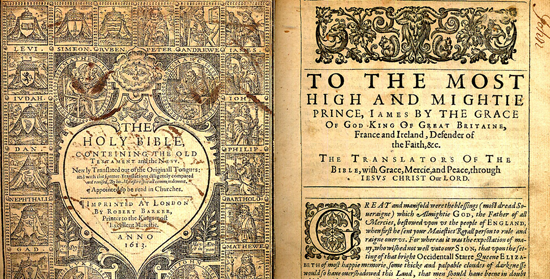

James called for the work to be done by the “best learned” of the universities and the church. The primary financier of the project was London printer, Mr. Robert Barker, who invested up to £3,500 pounds, for which he was awarded the copyright.

Although the king originally proposed 54 translators, the number was reduced to 47 during the three years before formal work began. The translators were divided into six committees: three for the Old Testament, two for the New Testament, and one for the Apocrypha.

Fifteen rules for translation were provided, which reflect, at least to some degree, the preferences of James I:

-

The ordinary Bible read in the Church, commonly called the Bishops Bible, to be followed, and as little altered as the Truth of the original will permit.

-

The Names of the Prophets, and the Holy Writers, with the other Names of the Text, to be retained, as nigh as may be, accordingly as they were vulgarly used.

-

The old Ecclesiastical Words to be kept, viz. the Word Church not to be translated Congregation &c.

-

When a Word hath divers Significations, that to be kept which hath been most commonly used by the most of the Ancient Fathers, being agreeable to the Propriety of the Place and the Analogy of the Faith.

-

The Division of the Chapters to be altered, either not at all, or as little as may be, if Necessity so require.

-

No Marginal Notes at all to be affixed, but only for the Explanation of the Hebrew or Greek Words, which cannot without some circumlocution, so briefly and fitly be express’d in the Text.

-

Such Quotations of Places to be marginally set down as shall serve for the fit Reference of one Scripture to another.

-

Every particular Man of each Company, to take the same Chapter, or Chapters, and having translated or amended them severally by himself, where he thinketh good, all to meet together, confer what they have done, and agree for their Parts what shall stand.

-

As anyone Company hath dispatched anyone Book in this Manner they shall send it to the rest, to be consider’d of seriously and judiciously, for His Majesty is very careful in this Point.

-

If any Company upon the Review of the Book so sent, doubt or differ upon any Place, to send them Word thereof; note the Place, and withal send the Reasons, to which if they consent not, the Difference to be compounded at the General Meeting, which is to be of the chief Persons of each Company, at the end of the Work.

-

When any Place of special Obscurity is doubted of Letters to be directed, by Authority, to send to any Learned Man in the Land, for his Judgement of such a Place.

-

Letters to be sent from every Bishop to the rest of his Clergy, admonishing them of this Translation in hand; and to move and charge as many as being skilful in the Tongues ; and having taken Pains in that kind, to send his particular Observations to the Company, either at Westminster, Cambridge or Oxford.

-

The Directors in each Company, to be the Deans of Westminster and Chester for that Place; and the King’s Professors in the Hebrew or Greek in either University.

-

These translations to be used when they agree better with the Text than the Bishops Bible. Tindoll’s. Matthews. Coverdale’s. Whitchurch’s. Geneva.

-

Besides the said Directors before mentioned, three or four of the most Ancient and Grave Divines, in either of the Universities, not employed in Translating; to be assigned by the Vice-Chancellor, upon Conference with the rest of the Heads, to be Overseers of the Translations as well Hebrew as Greek, for the better Observation of the 4th Rule above specified.

The Work Initiated

The work began in 1607. Each committee member translated the same section individually, and then met as a committee to review, discuss, and agree on the preferred rendition.

After the initial translation, a 12-member review committee revised the entire work. The review process continued for nine months. Two of the Review Committee members superintended the work during the printing process, which took an additional two years. It was published in May 1611.

The Work Explained

Realizing their work could be viewed with suspicion, the translators wrote a rather lengthy preface—the Translators to the Reader—to explain their intent for producing a new translation. In order for people to be able to meditate on Scripture, translation was necessary. “But how shall men meditate in that, which they cannot understand? How shall they understand that which is kept close in an unknown tongue?” In defense of being accused of heresy for daring to make a translation of the Scriptures, they cited the example of the Septuagint, recognizing it was not a perfect work, but still a useful one:

The translation of the Seventy dissenteth from the Original in many places, neither doth it come near it, for perspicuity, gravity, majesty; yet which of the Apostles did condemn it? Condemn it? Nay, they used it, . . . which they would not have done, nor by their example of using it, so grace and commend it to the Church, if it had been unworthy of the appellation and name of the word of God. [1]

To those who questioned the validity of a translation, they replied:

Now to the latter we answer; that we do not deny, nay we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English, set forth by men of our profession

. . . containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God. As the King’s speech, which he uttereth in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian, and Latin, is still the King’s speech, though it be not interpreted by every Translator with the like grace, nor peradventure so fitly for phrase, nor so expressly for sense, everywhere . . . . No cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current, notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it. [2]

There is no record of the translation being presented to the Privy Council or being ratified by the royal authority, in accordance with the king’s original order. However, since the Bishops’ Bible was not printed after 1611, the King James Version (KJV) became the largest English Bible in publication, thereby making it the official Bible to be used in churches, in accordance with the king’s 1541 Injunction. Some scholars consider this the technical “authority” for the 1611 Bible. In this view, the KJV is authorized more by default than by fiat. The king’s printer apparently had some justification for asserting it was “appointed to be read in churches.” There does not seem to be any challenge to this claim, and it is clear the publication was the result of the king’s Hampton Court Conference. So, while there may not have been a final official ratification, it seems reasonable to conclude that the 1611 Bible enjoyed royal sanction. This was only the fourth English Bible to have royal license of any sort.

The Work Revised

The first major revision of the King James Bible was produced at Cambridge in 1629. It expanded the marginal notes concerning the text and gave attention to punctuation and italics. The 1638 Cambridge revision made extensive revision of text, italics, and marginal readings.

The 1762 Cambridge edition included extensive revisions, but most copies were destroyed in a fire. A revised edition in 1769, printed in Oxford, built on that work became known as the Oxford Standard Edition. A host of other printings and revisions were produced in England and America, but none eclipsed the Oxford Standard, which is found in most King James Bibles today. Though frequently printed and revised, no other English Bible was produced between 1611 and 1881.

The Work Admired

It is widely accepted that the King James Bible is the most printed book in history, with more than a billion copies printed. Although this number is impossible to prove, it illustrates the immense popularity of this version of the Bible. The KJV still accounts for about 15% of all American Bibles purchased.

The King James Bible served a significant role in shaping the English language and hymnody. For more than a century it has been lauded as “the noblest monument of English prose.” Numerous factors contributed to its popularity. It drew from the best scholars in biblical languages of its day. A large committee, from various doctrinal views, diligently compared the existing translations to produce the rendering that best communicated the literal expression in the contemporary language. Its literary value and linguistic style was unequalled. Its prose and poetry worked its way into the every day language of the people. Lacking objectionable marginal notes, it was adopted by churches of varying theological positions. Along with being printed in a large pulpit size, it was also available in smaller editions, which made it affordable for personal use. In short, it appealed to the king, the church, and the home.

The fact that we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible is a testament of its enduring quality. It has served well for generations of English speaking believers. May the blessing of the KJV translators, to those who translated the Scriptures before them, be applied to their noble effort as well:

Therefore blessed be they, and most honoured be their name, that break the ice, and giveth onset upon that which helpeth forward to the saving of souls. Now what can be more available thereto, than to deliver God’s book unto God’s people in a tongue which they understand? [3]

About the Writer: Dr. Danny Conn is editorial director at Randall House Publications. Taken in part from, The Heritage of the English Bible, by Danny Conn, Ed.D., Randall House, 2011.

Endnotes

[1]

King James Version of the Holy Bible, “The Translators to the Reader” [book on-line] (London: Robert Barker, 1611, accessed 21 November 2010) available from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/bible/kjv.i_1.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

|

|